The Controversial Pursuit of Death Sentence by Indian government for Yasin Malik

December 17, 2024Is justice being served, or is the pursuit of Yasin Malik’s death sentence a political vendetta cloaked as law?

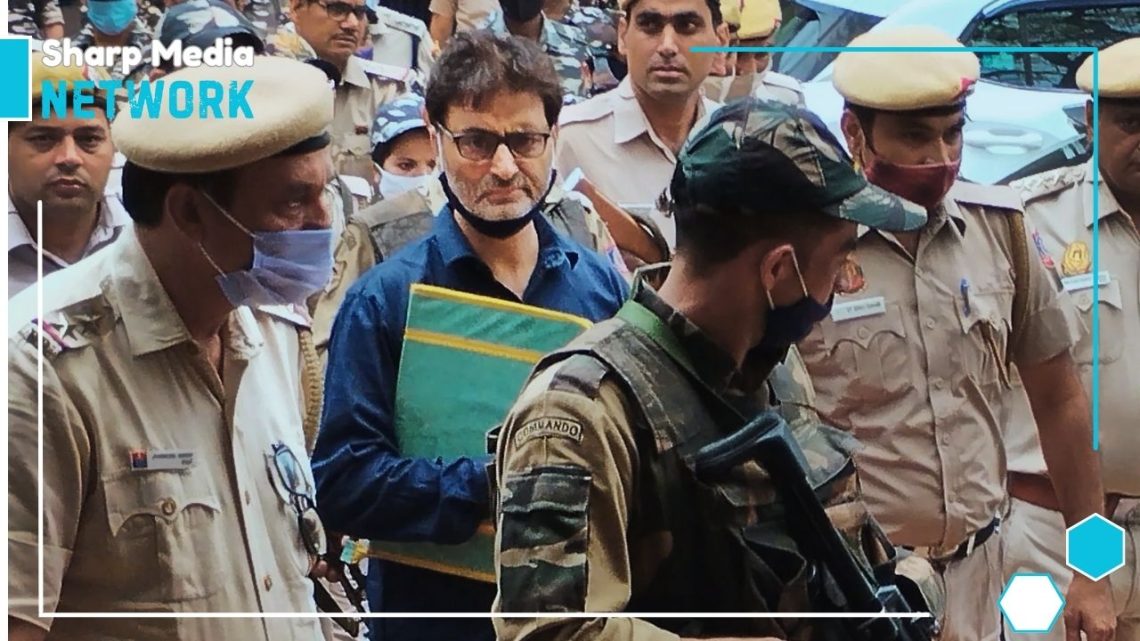

The case against Yasin Malik, the chief of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), for a crime dating back 34 years, has resurfaced, sparking questions about justice, political motives, and the rule of law. The Modi government’s demand for the death sentence against Malik is rooted in the 1990 attack on Indian Air Force (IAF) personnel at Rawalpora in Srinagar. On January 25, 1990, at around 7:30 AM, three armed men approached IAF personnel waiting for transport and opened fire, killing four and injuring 22 others.

The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), within days of the incident, alleged that Yasin Malik and others, including Javed Ahmed Mir and Mushtaq Ahmed Lone, orchestrated the attack. Five others were also implicated as co-conspirators. Over the past 34 years, the case has remained dormant due to a consistent lack of credible evidence. Courts have repeatedly released the accused, citing insufficient proof. However, in March 2020, just months after the abrogation of Article 370, the Indian government revived the case, charging Malik and others under criminal conspiracy. Malik’s decision not to contest the charges led the trial court to award him life imprisonment. Importantly, the court rejected the death penalty, ruling that the incident did not meet the “rarest of rare” standard required for capital punishment.

The government’s renewed efforts to push for Malik’s execution took a more aggressive turn a year later. Solicitor-General Tushar Mehta argued that Malik’s actions justified the death sentence on two grounds: his alleged participation in the attack and his attempt to “separate one part of the country from the rest of it.” Mehta further accused Malik of manipulating the court process by pleading guilty to avoid harsher punishment. He went on to connect Malik to unrelated incidents, including the kidnapping of Mufti Mohammad Sayeed’s daughter in 1990, which purportedly led to the release of terrorists responsible for the 2008 Mumbai attacks. These claims were proven misleading, as both David Headley and Tahawwur Rana had confessed to orchestrating the Mumbai attacks independently.

A key feature of the government’s case relies on the testimony of two witnesses—Rajwar Rajeshwar Singh, a corporal in the IAF who survived the attack, and Nirmal Khanna, the widow of Squadron Leader Ravi Khanna. Both testimonies, however, raise significant doubts. Initially, Rajeshwar Singh admitted to being in too much pain to recall details of the attack. Yet, 34 years later, he claimed to have seen Malik pull out a gun from under his ‘pheran’ and fire. This sudden clarity after decades of silence raises legitimate concerns about the reliability of his statement.

Nirmal Khanna’s account also invites scrutiny. She stated that Flight Lieutenant B.R. Sharma, a colleague of her husband, identified Malik as the attacker. However, inconsistencies plague this version. Sharma’s existence itself remains questionable. Official records show that one Baldev Raj Sharma died in service in 1973, long before the 1990 incident. Another officer by the same name retired in 2002 and passed away in 2016, casting doubt on whether he could have been present at the scene. Moreover, the CBI files lack any mention of Sharma’s testimony, and no independent evidence has been produced to validate Khanna’s claims.

The situation becomes even murkier when considering the circumstances of the attack. The shooting occurred in pre-dawn twilight at 7:30 AM, with temperatures plunging to minus three degrees Celsius. In such conditions, it is implausible that anyone could clearly identify an attacker’s face, as mufflers and winter clothing would have obscured their features. This casts further doubt on the credibility of visual identification, especially decades after the fact.

These inconsistencies underscore a deeper concern: the politicization of the judicial system in India, particularly in sensitive cases involving Kashmir. Despite no new concrete evidence, the Indian government’s pursuit of the death penalty against Malik appears more reflective of political vendetta than genuine justice. Malik, who led a peaceful human rights movement after JKLF declared a unilateral ceasefire in 1994, is now being targeted for refusing to accept the Indian narrative on Kashmir.

The international media has not overlooked these developments. Outlets like Al-Jazeera have labeled the case as “political vendetta,” noting India’s increasing use of the judiciary as a tool to silence dissent in Jammu and Kashmir. Malik’s conviction on a decades-old case is not an isolated incident but part of a broader trend where dissenting Kashmiri leaders are marginalized, and their voices are systematically suppressed.

The resurgence of this case serves as a stark reminder of India’s evolving authoritarian tendencies, where justice is manipulated to serve political objectives. For decades, figures like Maqbool Bhat and Afzal Guru have become symbols of a judicial system marred by political interference. Yasin Malik’s trial now risks adding another chapter to this legacy. The Indian government’s approach not only undermines the integrity of its legal system but also invites international criticism for its disregard of human rights and due process.

There is an urgent need for international scrutiny and pressure to ensure that the judiciary in India remains independent and fair, particularly in politically sensitive cases. The arbitrary revival of decades-old allegations against Malik reflects a troubling mindset that prioritizes political retribution over justice. At its core, this case reveals the challenges of dissent and autonomy in a region grappling with decades of conflict. For a democracy that prides itself on fairness and rule of law, India’s handling of Malik’s case raises uncomfortable questions about its commitment to these very principles.