India’s Water Gambit: Tulbul Revival and IWT Abandonment Ignite Regional Tensions

June 27, 2025India abandons Indus Waters Treaty, revives Tulbul project and eyes river diversions. Explore the explosive implications for Kashmir, Pakistan, and regional stability. Is a water war looming?

New Delhi has thrown down the gauntlet. In a move rippling with geopolitical tension, India’s BJP government declared it will not restore the landmark 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), simultaneously greenlighting the controversial revival of the Tulbul Navigation Project in Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK). This twin decision, framed by Water Resources Minister CR Paatil’s blunt assertion that “Water will not go anywhere. The treaty will not be renegotiated,” marks a seismic shift in South Asia’s fragile water-sharing framework. The stakes? Nothing less than control over the lifeblood rivers of the Indus basin and the potential ignition of a full-blown regional water crisis.

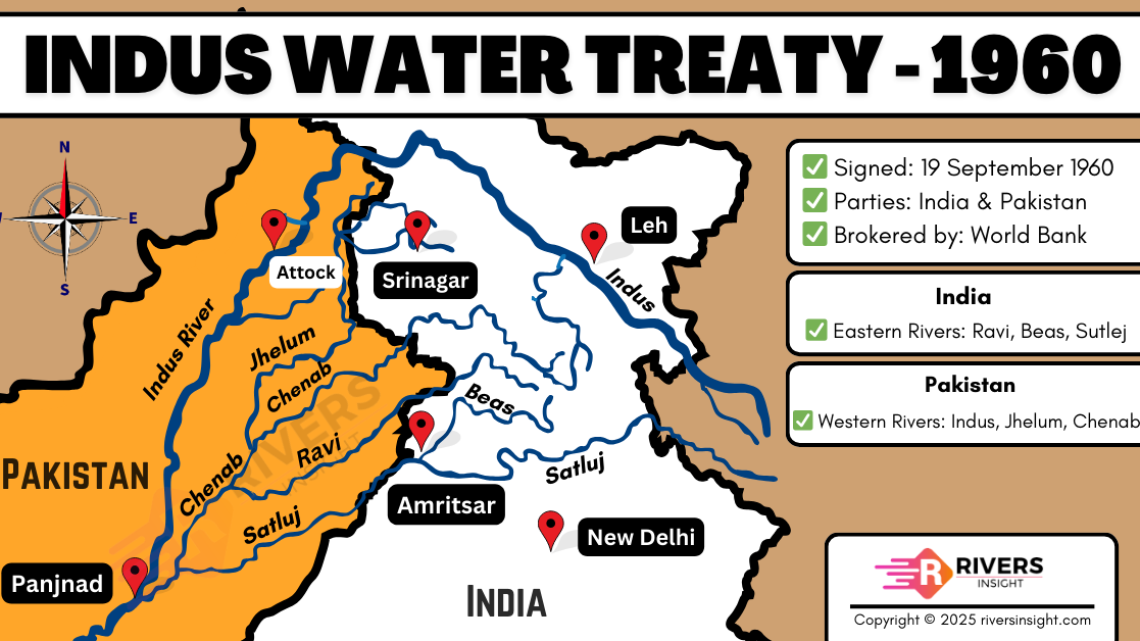

For over six decades, the Indus Waters Treaty, brokered by the World Bank, stood as a rare beacon of cooperation between nuclear-armed rivals India and Pakistan. It meticulously divided the six Indus basin rivers: granting Pakistan near-exclusive rights to the three “western rivers” (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab) crucial for its agriculture and survival, while India received primary rights to the three eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej). India’s rights on the western rivers were strictly limited to non-consumptive uses like run-of-the-river hydropower and minor storage. Indus Waters Treaty established the rules, however uneasy the peace.

India’s formal suspension of the IWT in April 2025 shattered that uneasy peace. Officials now openly admit this “abeyance” is strategic: “After the abeyance of the IWT, projects on the western rivers can be executed faster. We can now seek a greater share of the Indus waters from these and will try to find technical feasibility to do so,” a top source revealed. This isn’t just rhetoric. Tulbul Project (Wullar Barrage) in Sopore, IIOJK, is now back on the fast track, with the NHPC preparing a Detailed Project Report (DPR). Designed to make the Jhelum navigable in winter, critics see it as a thinly veiled storage mechanism violating treaty limits. Furthermore, India lists Western Rivers Projects, confirming five previously stalled ventures are now moving ahead.

India’s formal suspension of the IWT in April 2025 shattered that uneasy peace. Officials now openly admit this “abeyance” is strategic: “After the abeyance of the IWT, projects on the western rivers can be executed faster. We can now seek a greater share of the Indus waters from these and will try to find technical feasibility to do so,” a top source revealed. This isn’t just rhetoric. Tulbul Project (Wullar Barrage) in Sopore, IIOJK, is now back on the fast track, with the NHPC preparing a Detailed Project Report (DPR). Designed to make the Jhelum navigable in winter, critics see it as a thinly veiled storage mechanism violating treaty limits. Furthermore, India lists Western Rivers Projects, confirming five previously stalled ventures are now moving ahead.

The ambition extends far beyond navigation. Indian officials confirmed active consideration of River Diversion Plans aimed at maximizing India’s use of its “share” from the western rivers. The most explosive proposal? Chenab River Diversion – a technically complex scheme linking the Chenab to the Ravi-Beas-Sutlej system via a new canal, potentially diverting water towards Indian Punjab and Haryana. While officials hastily add the Indus itself isn’t targeted, the intent is clear: aggressively harness waters historically flowing primarily into Pakistan. This comes alongside the aggressive push on hydropower: the Kishanganga Hydro Project (diverting Neelum/Kishanganga to the Jhelum basin) is operational, and the 850 MW Ratle Hydro Project on the Chenab is being accelerated.

Simultaneously, India is attempting to stall international oversight. The BJP government has formally requested Michel Lino, the World Bank-appointed neutral expert examining disputes over the Kishanganga and Ratle projects, to suspend proceedings. This move, seen by analysts as an attempt to create legal vacuum while pushing physical changes on the ground, leaves the World Bank in a precarious position. Its silence thus far speaks volumes about the diplomatic quagmire unfolding. Imagine the anxiety downstream as the legal safeguards crumble and bulldozers move in upstream. The rivers aren’t just water; they are Pakistan’s agricultural backbone and drinking water source for millions.

The facts are stark. Pakistan is one of the world’s most water-stressed nations, heavily reliant on the Indus system. Significant reductions in flow, whether through storage (like Tulbul), diversion, or hydropower consumption (altering timing and volume), pose an Existential Threat to its food security, economy, and societal stability. As noted by numerous international water security experts, transboundary water disputes are potent catalysts for conflict, especially in regions with existing tensions. For Kashmiris living under occupation, these projects represent further exploitation of their resources and environmental disruption, deepening their grievance. The human cost – farmers without water, communities displaced, ecosystems destroyed – is immense and often overlooked in geopolitical power plays.

India’s calculated abandonment of the Indus Waters Treaty and its aggressive pursuit of the Tulbul revival and western river projects mark a dangerous new chapter in South Asian hydro-politics. This isn’t merely a technical dispute; it’s a high-stakes gambit with profound humanitarian, environmental, and security implications. The revival of Tulbul and the specter of river diversions aren’t just infrastructure projects; they are potential triggers for instability in an already volatile region. The World Bank’s next move, Pakistan’s response, and the international community’s engagement will be critical in determining whether this crisis descends into conflict or finds a path back to negotiated water security. The flow of these rivers now carries the weight of potential disaster.