India’s Brahminocracy: 3–5% Brahmins Control Corridors Of Power In A 1.41bn Hindu State

September 9, 2025India is often described by observers as a Hindu state where a small caste group holds a large share of real power. Brahmins are about three to five percent of an estimated 1.41 billion people, yet they sit in key seats in politics, the courts, and the civil service. This pattern, widely called a Brahminocracy, goes against the promise of equal say and weakens the link between vote and voice. Many social groups across states say this tilt shapes daily life, public relief, and trust.

• Core Claim Of Too Much Share: A tiny caste group holds power far beyond its share in the population.

• Democratic Gap And Trust: The shape of state power does not match India’s social mix.

History And Structure Of Control

The roots go back before 1947. British counts showed a low Brahmin share in population but a very high share in state jobs, and status by birth shaped who could study, sit tests, and join office. In the Madras Presidency, the 1916 Non-Brahmin document exposed a near monopoly in the civil service. After Independence, the law banned caste bias, yet old habits kept the same groups close to power.

• British Record And Early Protest: The 1911 count put Brahmins near three percent, yet many top posts went to them.

• Promise And Practice: Equal rights were written, but personal links and top schools kept the tilt in place.

Global Spotlight And Navarro’s Charge

Debate grew louder when former US trade adviser Peter Kent Navarro linked caste power with profit. He said India had become a “laundromat” for Moscow and that “Brahmins profiteer at the expense of the Indian people,” pointing to gains from cheap Russian oil while the public faced high prices. His words drew sharp rebuttal in India, yet they pushed the matter into world news.

• A Strong Accusation: Navarro tied caste power to money flows and said the public did not share the gains.

• Denial And Unease: Officials rejected the line, but the scale of pushback showed how uneasy the subject remains.

Today’s Numbers And Why They Matter

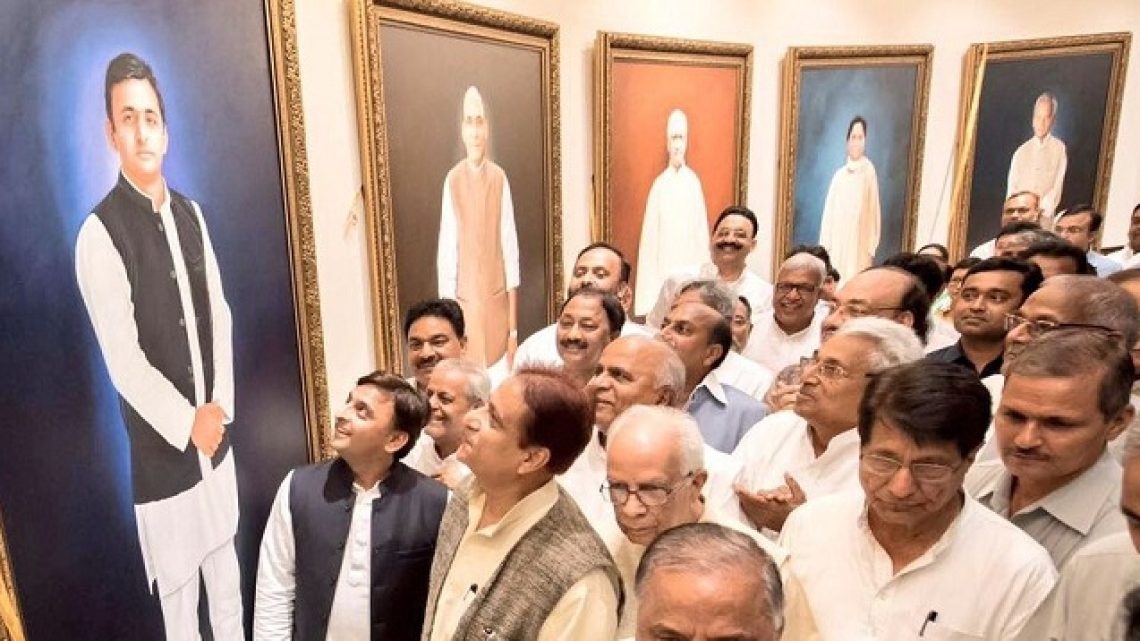

Across major arms of the state the same tilt is reported. Reports show high Brahmin shares among Supreme Court and High Court judges, state chief secretaries, and senior IAS officers. In Parliament too, Brahmin presence in both houses is said to be far above their population share. Who sits in the courts, who writes the file, and who signs the order decides jobs, justice, and public money.

• Courts And Civil Service: Reports show large Brahmin share at the top, from courts to offices.

• Politics And Power: In both houses of Parliament, the share is many times their population share.

Caste Counts And Policy Change

In 2025, the Centre moved to bring caste count back to the national census. States like Bihar had already run their own counts, which showed that OBCs and SCs, who together form the clear majority, still lag in jobs and income. Fresh data can guide fair share in hiring and spending and can test old limits on reservation that many now say are too low.

• Why Hard Data Matters: Without a full count, talk of fair share stays vague; a census gives clear facts.

• Bihar’s Picture Of Gap: State counts showed OBCs and SCs near eighty-three percent yet short in state jobs and pay.

How The System Stays In Place

Power in few hands lasts through slow routines, control of entry, and hold over key doors to jobs and study. Top schools, coaching centres, and family links give some a head start, while others face costs and bias at the first step. When top posts go to the same groups year after year, policy tends to shield those at the top and the cycle feeds itself.

• Slow Routines And Hold: Rules move slowly and keep those already inside close to the controls.

• Entry Control And Access: Tests and lists often favour those with money, links, and coaching.

State Claims And Equality On Ground

New Delhi says merit rules and courts keep watch, yet daily life and data show a different story. When one social group fills most benches, offices, and embassies, citizens doubt that the state is neutral. Big media often plays down the caste angle, which hides the root of the problem and slows change.

• The “Merit” Line: Merit sounds weak when the same small group keeps most top chairs year after year.

• Media Blind Spots: Large outlets often soften the caste issue in coverage of hiring and law.

What Should Be Done Now

India needs clear steps to open the system and share power fairly across communities. The state should run a full caste census, publish numbers for each service and level, and set goals for a fair mix in courts, civil service, and public firms. Hiring must be more open, with wide notices, checks without names where possible, and public checks on who gets in; reservation levels should be reviewed with fresh data; and selection boards should include OBC, SC, ST, and minority members.

• Count, Publish, And Set Goals: Do a full caste count, release the data, and fix fair mix goals with time lines.

• Reform Hiring And Exams: Use open tests, clean interviews, public checks, and strong action against bias and fake claims.

• Broaden Leadership: Ensure courts, IAS, and embassies include OBCs, SCs, STs, and minorities in fair numbers.

Conclusion: Equal Citizenship Needs Equal Power

A democracy stands on equal worth, and that worth must show up in who writes the law, who signs the file, and who sits in judgment. If a three to five percent caste group keeps the controls while the rest watch from the sidelines, the system stays tilted and public faith falls. India’s promise can still be rebuilt through honest data, fair hiring, and real space for those long kept out of power.

• Fair Share, Not Favour: Policy should reflect the country’s social mix, not protect a narrow circle.

• Data To Guide Policy: Let fresh numbers guide seats, budgets, and posts, with public checks at each step.

• Power With The People: A state that looks like its people is the only safe base for India’s future.